The name Leopold Godowsky is rarely mentioned when one talks about favourite composers who wrote piano works. His compositions are often only explored by pianists who are interested in the exotic repertoire of the piano literature. Does Godowsky deserve this neglect? Perhaps not. He might have been the most unique writer of piano music after Chopin, and that's not forgetting Liszt, Debussy and Rachmaninoff. So why is Godowsky's music not as well-known as that of the composers mentioned above?

Before discussing Godowsky's music proper, some mention of his pianistic abilities should be made. In an age where great pianists, including Josef Hoffman, Sergei Rachmaninoff and Arthur Rubinstein reigned supreme, all conceded that Godowsky had the most perfect pianistic mechanism of his time, and very likely of all time. Godowsky was probably unequalled in independence of hands, equality of finger and his ability to delineate polyphonic strands. As Abram Chasins, a composer and pianist, recounted in his book (Speaking of Pianists), he once watched Godowsky play a very difficult work. ‘Godowsky's effortless mastery made me unaware of the vastness of his pianistic feat…Years later, I realised it…with what devastating ease Godowsky had disposed of it, making it seem like nothing at all.'

Perhaps because he was equipped with such an all-encompassing technique, he wrote music that is technically very difficult to execute, though it is never difficult for the sake of it (more below). Yet, despite their difficulties, it is not flashy or showy music. Even though many pianists nowadays have the technical chops to perform Godowsky's music, it has been neglected in favour of music which is outwardly showy. As such, there has been a shortage of recordings and performances of Godowsky's music. Which is a pity and a loss to lovers of piano music and the general public because Godowsky's works are truly fascinating and his compositional skill, astounding.

Below is a brief introduction to two of Godowsky's most famous works, by which he is primarily remembered for today. They also illustrate his ingenuity in writing music for the piano.

1. 53 Studies on Chopin's Études

Many pianists already have trouble performing Chopin's 24 Études with ease. Godowsky probably didn't think they were difficult enough and used Chopin's Études as a template to write new works. The final result was the 53 Studies, which Harold Schonberg (a well-known critic for The New York Times) described as the 'most impossibly difficult things ever written for the piano…fantastic exercises that push piano technique to heights undreamed of even by Liszt.' It should be emphasized that in writing the Studies, Godowsky was not trying to 'improve' on Chopin's originals. Rather, as he wrote in the Preface to the Studies, the aim was ‘to develop the mechanical, technical and musical possibilities of pianoforte playing…' Two Studies are described below to illustrate how Godowsky achieved this through his creativity and ingenuity.

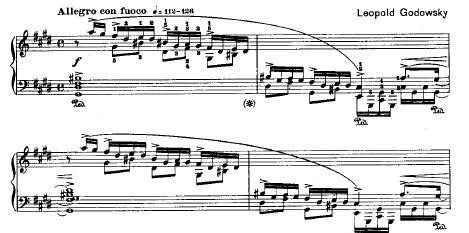

Chopin-Godowsky Study No. 22

This work is based on Chopin's 'Revolutionary' Étude, Op. 10 No. 12. Doesn't look too hard after all, does it? So what's the fuss? Check out the YouTube video below. It features a pianist who played the original Chopin 'Revolutionary' Étude and the Godowsky Study immediately after. (If you're familiar with the original Étude, jump to 2:45 to watch the performance of the Godowsky study.)

As Marc-André Hamelin, an incredible pianist who has recorded all 53 Studies, said of Study No. 22, "The transcriber's wizardry enables us to find here all the passion and the fury contained in the original*, and the blood, sweat and tears needed to convey that to an audience will be obvious to anyone glancing at the score."

*Godowsky's faithfulness to the spirit of the original étude is truly startling.

In case you didn't watch the video, the Study is supposed to be played by the left hand only(!). Out of the 53 Studies, 22 are for the left hand alone and Godowsky's comments on these Studies are worth quoting in full. (The comments which I feel are particularly insightful are marked out in bold.)

"In writing the twenty-two studies for the left hand alone, the author wishes to oppose the generally prevailing idea that the left hand is less responsive to development than the right. In its application to piano playing, the left hand has many advantages over the right hand and it would suffice to enumerate but a few of these to convince the student that it is a fallacy to deem the left hand less adaptable to training than the right hand. The left hand is favoured by nature in having the stronger part of the hand for the upper voice of all double notes and chords and also by generally having the strongest fingers for the strongest parts of a melody. In addition to what is stated above, the left hand, commanding as it does the lower half of the keyboard, has the incontestable advantage of enabling the player to produce with less effort and more elasticity a fuller and mellower tone, superior in quantity and quality to that of the right hand."

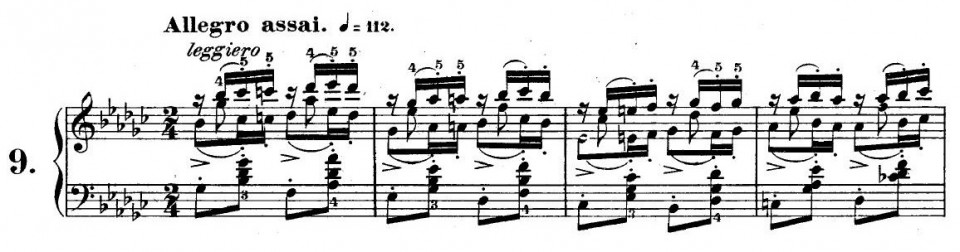

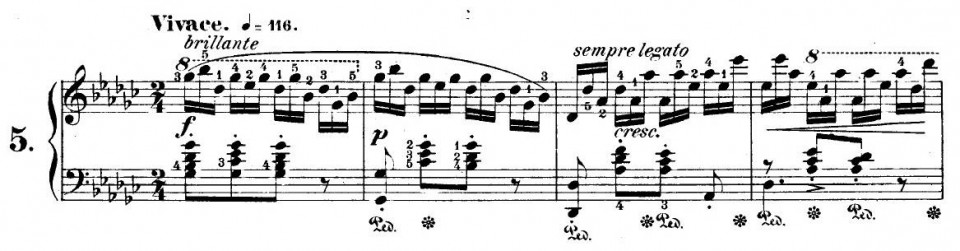

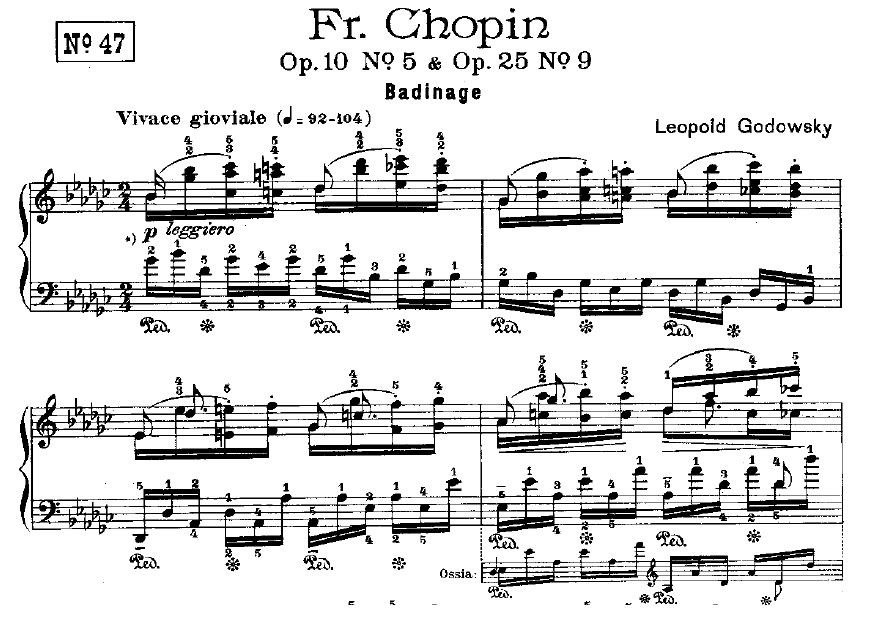

Chopin-Godowsky Study No. 47

An even more amazing Study is No. 47 where he combined two études, both in G flat major. Snapshots of the two original études are given. Check out the right hand parts of Figures 2(a) and 2(b) and compare it to Godowsky's creation (Figure 2(c)).

Hamelin again, "It seems quite plain to me that such a fantastically clever feat of combinatorial wizardry could only have been achieved by somebody with a truly profound knowledge and love of his chosen material. To me it can only inspire admiration."

The interweaving of the two etudes actually sounds wonderful! One may wonder why Chopin himself did not do it. And watching the pianist’s side profile in the video, the work doesn’t appear very difficult, does it? Imagine slogging to learn and perfect this Study, only to appear doing nothing very much to an audience while performing it!

The other 51 Studies feature all kinds of amazing transformations of Chopin's études. Godowsky has been accused of sacrilege for writing these Studies, i.e. he mutilated the beauty and purity of Chopin’s original works. Whether this is the case is for academics to argue over. Whatever it is, it is hard to dispute the compositional skill and ingenuity which Godowsky poured into these Studies.

2. Passacaglia

"It's hopeless! You need six hands to play it."

- Vladimir Horowitz

So Horowitz said of the Passacaglia. The above statement is certainly not true but it still remains a formidable work which requires a pianist of an unusually fine technique to execute. Godowsky used the opening 8 measures of Schubert's "Unfinished" Symphony as the theme, composed 44 variations based on it, (of course, heaping difficulty upon difficulty on succeeding variations) and concluded the work with a cadenza and a fugue.

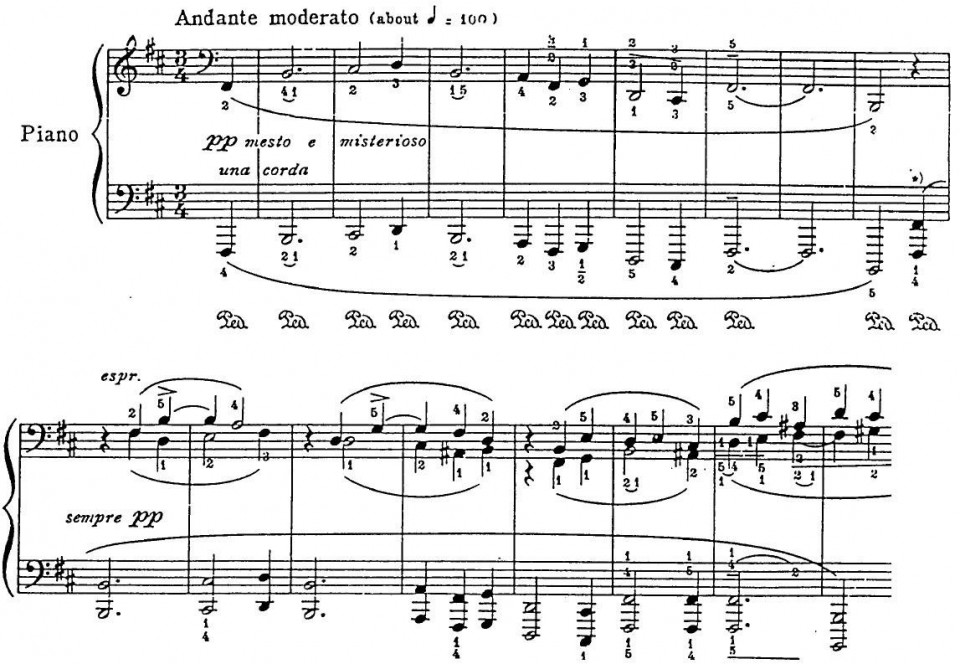

The work opens innocently enough, with the theme presented in both hands (first 8 bars), and it is followed immediately by the 1st variation (Figure 3(a)). The theme is in the left hand, while the right hand introduces counter melodies. The 'density' of the writing gradually increases and a late variation is shown in Figure 3(b).

Many of the variations feature such dense contrapuntal writing. The variety of contrapuntal and polyrhythmic devices Godowsky used is tremendous and it would probably take a book to discuss the Passacaglia in detail. In the more complicated variations, among the mass of notes, Schubert's simple theme can almost always be found and should clearly be heard amidst the whirlwind of sound (as a result of the decorative writing). That would require a pianist who has excellent control over the volume of every note he/she is producing. Perhaps the task of learning and mastering such a work is too unrewarding, which may be why the Passacaglia is not heard frequently in the concert hall today.

A performance of the Passacaglia is shown in the embedded YouTube Video below:

Godowsky also arranged many works by J. S. Bach (violin sonatas, cello suites), Schubert (Lieder) and other composers for solo piano. He also composed a number of original works. It includes a large-scale Piano Sonata, Java Suite (musical portrayal of his impressions of Java) and two sets of charming miniatures, Triakontameron and Walzermasken, similar to Schumann’s Carnaval or Davidsbündlertänze.

Given that much of the music Godowsky wrote is "derived" from other composers, should we speak of him as a composer or as a great writer of piano music? After all, his best-known works today (the 53 Studies, Passacaglia, transcriptions) are fantastic elaborations on works by other composers, rather than original melodies that he himself composed. However, such writing could only have been achieved by a pianist who had an intimate knowledge of the possibilities and limitations of the instrument and piano technique. Such difficult music is probably out of reach technically for most of us, but it is nonetheless a fascinating experience exploring, listening to and appreciating the music written by one of the most unique figures in the history of the piano.